The winner takes it all – ecological consequences of belowground networks

Many plant root systems are connected by mutualistic fungi exchanging plant carbon versus soil nutrients. What are the ecological consequences of these connections? Is it really “socialism in soil” or a “belowground sharing economy”? Studies at the university of Miami demonstrated that nature at least sometimes may be more like Manchester capitalism.

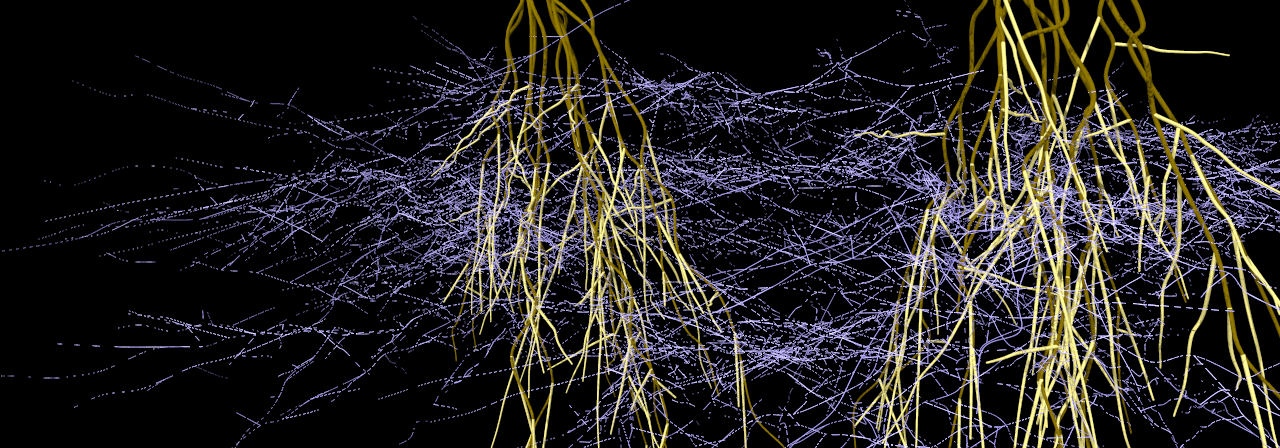

Mineral nutrient acquisition in the soil is based for many plants on symbiotic (mycorrhizal) fungi. Fungal hyphae are more efficient than plant roots in extracting mineral nutrients from a given soil volume. Plants in turn often have large stocks of what fungi desperately need: carbohydrates. The exchange of these two goods has been studied for a long time in a very simple setting: one plant interacting with one fungus. In nature, however, many fungi are interacting with many plants at the same time. The implications of this complex situation will keep scientists busy at least for the next decades.

Scientists from the university of Miami now studied an artificial setting, where they grew one grass species (Big Bluestem) together with a number of mutualistic fungal strains, allowing or preventing fungal connections between the plants. Some of the plants were shaded during the experiment. These plants could only transfer reduced amounts of carbohydrates to their fungal partners. Shaded plants of course grew weaker than fully illuminated plants and this difference was enhanced when allowing the formation of mycorrhizal networks. At the same time scientists could demonstrate that mycorrhizal networks transfered nitrogen from the containers of shaded plants to fully illuminated plants. Mycorrhizal fungi apparently had rewarded plants able to provide high amounts of carbohydrates by providing particularly high amounts of nitrogen in return. By doing so, they increased competition and inequalities between neighbouring plants. While this is an interesting result, it should be kept in mind that it was obtained under relatively simple greenhouse conditions. Whether the observed effect is really relevant under field conditions still remains to be seen.

Source: New Phytologist DOI: 10.1111/nph.14041